Alemanen kanposantue

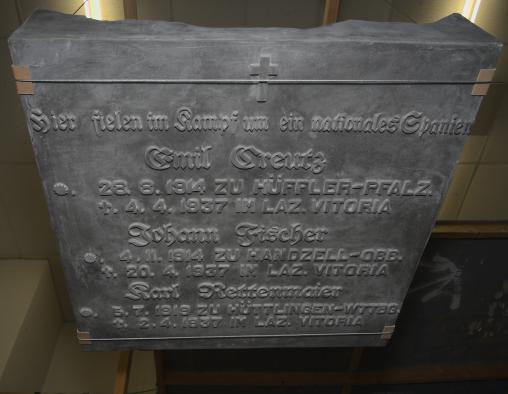

“Alemanen kanposantue” is colloquial Basque for “the graveyard of the Germans”. It is also the name given by locals to a memorial stele from the Spanish Civil War that stood forgotten and neglected by the side of a road in rural Basque Country, and into which once were engraved the names of three German soldiers who belonged to the Condor Legion of the Luftwaffe.

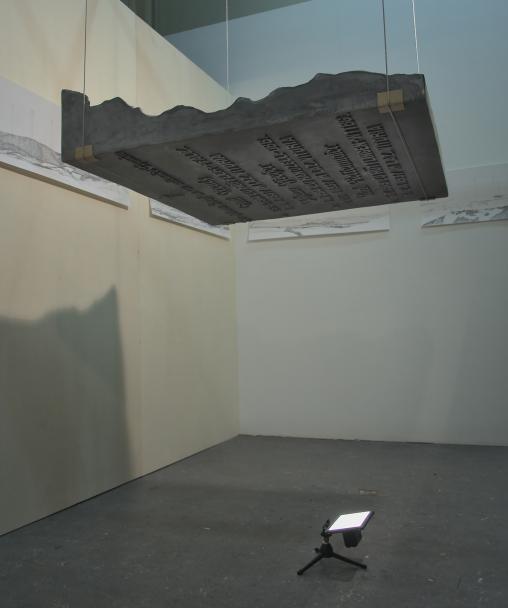

The surface of the monument has been chipped and damaged by years of vandalism and accumulating layers of political graffiti. We have made a sculptural reproduction of this surface, treating it as a palimpsest of all the informal attempts to dismantle and appropriate the ideologically laden object.

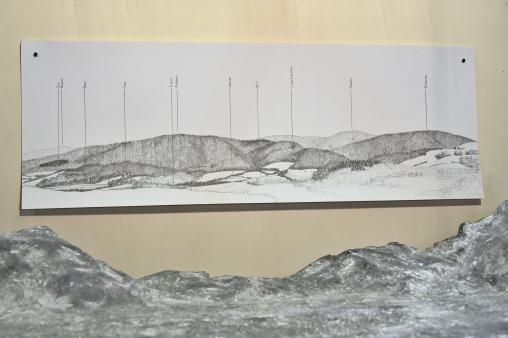

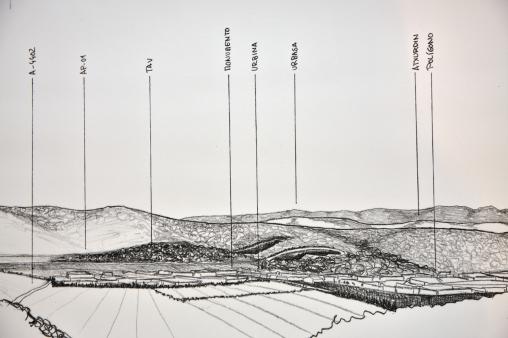

The sculpture is combined with a series of pencil drawings in which we map the “guilty landscape” that surrounds the stone, in a style that closely follows that of original military sketches of the front line during the war.

By the side of the road somewhere in rural Basque Country, where the plains of Álava roll into the mountains of the north, stood until recently a weathered stone memorial from the Spanish Civil War. Most of the locals have long forgotten what was commemorated by the surly block of marble, and it has served mainly as a support for layers and layers of political graffiti. Endorsements of radical separatist movements are regularly painted over with fascist symbols of Spanish nationalism, and vice versa.

Memories of the Civil War and of the dictatorship that followed it are still politically sensitive subjects in Spain. We have been investigating the material remains of this uncomfortable heritage since 2015, and this research has brought us in touch with different archaeologists who share similar interests. One of them happens to have studied the provenance of the stone, and he wrote an article about his findings in the local newspaper.

During the Civil War the front line ran across the foot of the mountain range in which the Republican troops had entrenched themselves. General Franco’s army received military support from Nazi-Germany at the time, and back then there was a guard post in place of the monument, manned by three young soldiers from the infamous Condor Legion.

They must have seen the airplanes fly overhead with their deadly cargo. Picasso immortalised the destruction caused by these bombers among the defenseless population of Guernica in what was to become one of his most famous paintings. But the three soldiers didn’t survive the German terror bombing campaign either. According to the archaeologist they succumbed to “friendly fire”. The Germans left a stone in their memory, with their names carved out in ornamental Gothic letters.

It is a fascinating footnote in the history of one of the most traumatic events of the twentieth century. But our interest in the obscure and forgotten monument was only really roused when we found out that a few weeks after the article had been published, someone had taken the effort to anonymously chisel out the last visible remains of these letters.

What provoked this person, or persons, to erase these traces from the past? Was it an attempt to destroy material evidence of the German presence during the Civil War? Franco’s regime has always denied receiving their military aid, and circulated propaganda at the time that blamed “the Bolsheviks” for setting fire to their own houses.

Former trenches run like scars through the surrounding mountain terrain. Among them one is likely to stumble over a wide variety of memorials, both official and informal. This is where not only the Civil War is being commemorated, but also the leaden years of the Basque conflict that followed the dictatorship. At the top of the nearest mountain, for instance, a pole sticks out of the ground in memory of a young ETA member who died in a shootout with the police in 1991. The Basque flag that it should be bearing is regularly torn down by disapproving passers-by.

The anonymous intervention on the Nazi monument in the valley should therefore probably not be read as an attempt to conceal that which has long since ceased to be a secret. It is rather the continuation of an ideological struggle over public space that is still very much alive: The illegible stone as a polysemic demarcation of territory.

In 2017 we decided to create a three-dimensional “snapshot” of the monument. We crafted a silicone mold around the stone in order to create a detailed reproduction of its surface. Just in time, we discovered, because shortly afterwards the silent, massive block disappeared entirely. All that physically remains as a reminder of the plight of the three soldiers is located in our studio in Rotterdam.

We have produced an object with this mold that is less a copy of what we encountered in the field than an embodiment of the transience of the monument itself. At the hand of old archival photographs we reconstructed the original German inscription and used this to create a sculpture that combines both the original state of the stele in 1937 and its decay over time.

The sculpture is thus a “negative” of the original: it is made up of the residual space formed by each letter that was scratched out, and by every indentation that was struck into the rock. On one side it preserves the undamaged text with its black letter typeface, and on the other the ragged and broken surface of the stone at the end of its existence.

We have also returned to the site where the original monument once stood, in order to map the “guilty landscape” around it, with its rugged mountain slopes and overgrown trenches. Exploring old strategic vantage points, we have created a series of panorama drawings in a style that closely follows that of original military sketches of the front line in 1937.

By juxtaposing these drawings with our rendition of the Nazi monument, we wish to establish a link between the history of human violence at the site and the centuries of geological processes that have given it its shape.

Acknowledgments

Alemanen kanposantue was produced with support from:

- Mondriaan Foundation

- Jan van Eyck Academy / NEARCH - New Scenarios for a Community-involved Archaeology

- Azala Kreazioa Espazioa

- Galeria LaTaller